Chapter 2 - How Kubernetes CPU Requests and Limits Actually Work

Chapter 2 of a wizard's journey through the technical inner workings of Kubernetes Resource Management

Understanding the mysterious inner workings of Kubernetes resource management at a deep level can make you feel like a wizard. As detailed in the first chapter in this series, becoming a wizard of Kubernetes resource management involves achieving an end-to-end contextual understanding of how resource management functions in Kubernetes, including everything from its user abstractions to technical implementation at the Linux kernel level.

In Chapter 1, we detailed how pod spec and node status are used to make matches between pending pods and available nodes. Once a match is made, the node needs to run the pod. Chapter 2 resumes with a deep dive into CPU, setting out to answer the question of how CPU resource requests and limits come into play at the Linux OS level and what that means in terms of anticipating, predicting or guaranteeing CPU resource outcomes.

The Journey Resumes #

Before we could get into the details of how requests and limits affect running containers, we had to cover how pods get scheduled to nodes. The most important takeaways about resources are that pods are assigned to nodes purely based on their resource request sizes and the node’s reported capacity size, and that node “fullness” is entirely request-based, having nothing to do with either resource usage or resource limits.

To pick up again, imagine that in your Kubernetes pod spec, you asked for 250 millicores (m) of CPU to run your container. Now that pod has been scheduled to run on a node with a node status that reports 1,930m of allocatable CPU capacity. Now what?

Something has to happen to turn that abstract request, 250m of CPU, along with any limits, into a set of concrete allocations or constraints around a running process. This is necessary because Kubernetes isn’t an operating system, it’s just an orchestrator. It will be up to Linux (as the actual OS), to enforce resource-related settings. But Linux doesn’t understand the requests and limits abstraction. A conversion is needed to configure the OS subsystem(s) responsible for actual enforcement.

Most Kubernetes resource abstractions are implemented by kubelet, and the container runtime, using Linux Control Groups (cgroups) and control group settings.

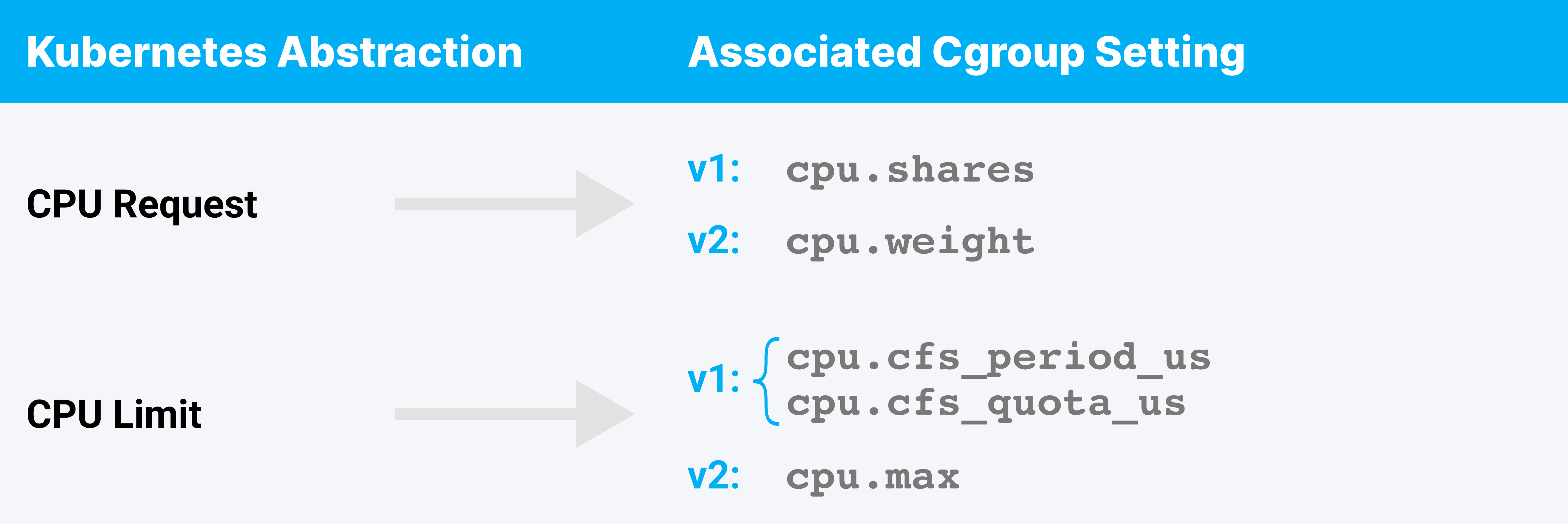

We’re focusing just on CPU right now. For CPU resources the relevant cgroup settings are:

Understanding the quirks of this conversion, from Kubernetes resource abstractions to enforceable Linux kernel cgroup parameters (or other configurables), can really uplevel your ability to predict behavior, debug issues and intelligently configure resource settings for your workloads.

Note: There are two versions of the cgroup API in common use. For simplicity, the remainder of this article will refer only to the cgroup v2 setting names. Use of the v1 implementation has functionally equivalent outcomes.

CPU Resources Are Complicated, Yo #

Believe it or not, the way low-level kernel facilities that control, allocate and reserve CPU time for a process work are not nearly as simple and easy to understand as “please give nginx 250 millicores, thx.”

Shocking, I know. 🤯

There’s neither time nor space in this article to dive very deep into the gory details of Linux’s Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS). I’m not going to tell you how to calculate the precise values that Kubernetes will set cpu.weight to on a given node for a given request value. Those articles are out there, and they are fascinating. I highly encourage you to dig in if you’re interested. Here’s a great example of one.

I will try to do justice, though, to constructing a conceptual model that’s directly useful in decision-making for Kubernetes workload resource settings. With that goal in mind, the most crucial foundational things to know are:

- Each of the CPU cgroup controls that Kubernetes uses relate to Linux’s Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS).

- CFS is a proportional process scheduler. Assuming we don’t put a finger on the scale, think of CFS as wanting to give every runnable process an equal amount of CPU time.

- When Kubernetes sets

cpu.weight(requests), that’s a finger on the proportional scale. If one runnable process has twice the weight of another, CFS will give the twice-weighted process twice as much CPU time. - When Kubernetes sets

cpu.max(limits), that doesn’t change the process’s proportional priority while it’s runnable. What it might do is cause the process to periodically be put in a time-out — like a petulant child — during which the process will not be given any CPU time at all.

Does that make any sense? Not really? Ok. Let’s unpack it piece by piece. First, what it means to put a “finger on the scale,” and then what it means to “put a process in a time-out.”

CPU Requests – Finger on the Scale #

Linux’s CFS might default to giving every runnable process an equal amount of CPU time, but that’s not what Kubernetes wants.

Kubernetes’ goal is for each container’s process(es) to be prioritized for the fraction of CPU time corresponding to what the user specified in their CPU resource request for the container.

Simplistically, on a single-core node (1,000m capacity): a container with a CPU request of 200m should be prioritized for ⅕ (one fifth) of the available CPU cycles; a container with a request of 250m should be prioritized for ¼ (one quarter) of the cycles; a container with 500m requests, ½ (one half) of cycles.

If the node capacity changes, so do these proportions. On a two-core node (2,000m) capacity, the same 500m request would mean the container should be prioritized for ¼ (one quarter) of the node’s available CPU cycles. There are more CPU cycles available on a two-core node, so the fraction that should be prioritized to run this container is smaller.

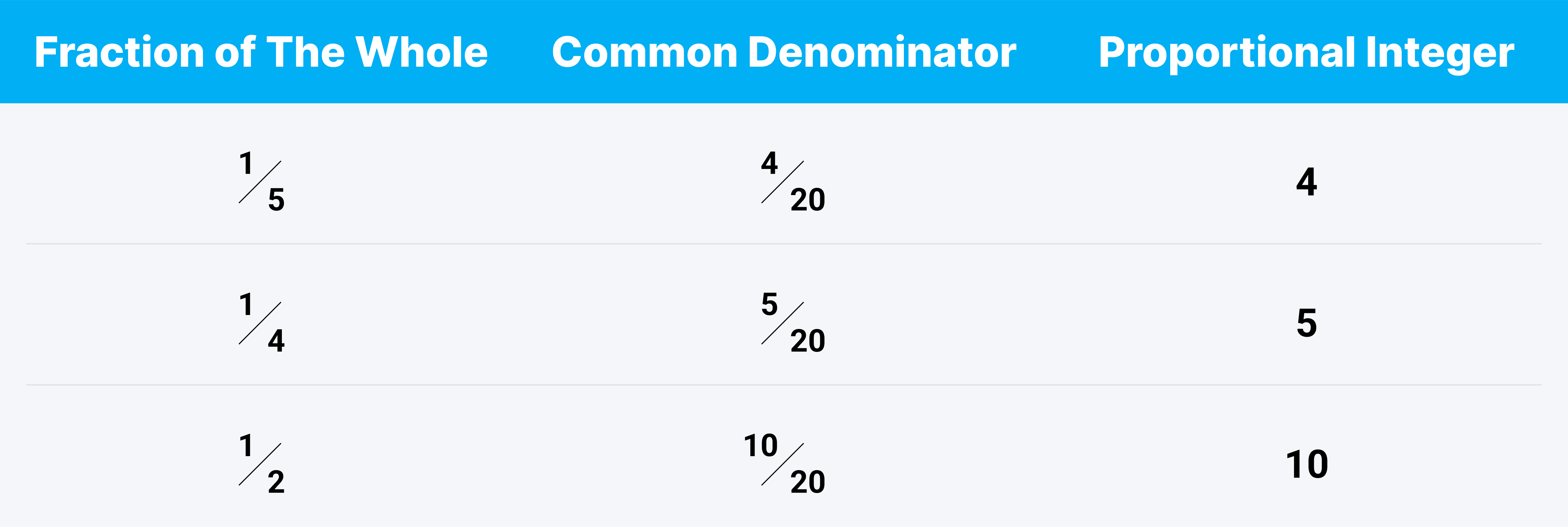

To transform CPU requests into something that can be implemented by the cpu.weight cgroup control, Kubernetes converts millicore values into capacity-proportionate weight values. What are those values specifically? That’s a great question.

Because cpu.weight values are inherently proportional to each other, there’s no magic value to set cpu.weight to that guarantees a static amount of CPU time. The proportional priority of any single process depends on its weight relative to other running processes.

To get integer weights from proportional fractions like ⅕, ¼, and ½ with each other you might calculate a common denominator and use it to get to your proportional integer cpu.weight values.

This model is conceptually similar to what Kubernetes does. Thanks to the way pod scheduling and node “fullness” is implemented, Kubernetes is assured that the fractional values it calculates for containers will never add up to more than one, so a cgroup’s CPU priority will never be less than its request-to-capacity proportion.

This is a working, though oversimplified, conceptual understanding of what Kubernetes does with CPU requests. We can make one very interesting observation about behavior at this level.

💡KEY OBSERVATION

Kubernetes CPU requests guarantee a minimum amount of CPU time.

When a node is “full,” and when every container on a node is running and contending for CPU time, each container will receive exactly the amount of CPU time specified by its CPU requests.

No container needs to have CPU limits for scheduling to work out this way. Proportional scheduling based on cpu.weight alone is sufficient to ensure this.

Quirk: Burstable Pods #

There is often moment-to-moment spare CPU capacity on a node that isn’t guaranteed to a particular container by virtue of its CPU requests. This happens when:

- The node isn’t “full” yet, so some of its capacity hasn’t been guaranteed to any particular container.

- A container has requested CPU resources, but isn’t using them at the moment.

When this happens, how do Burstable pods work? Assume multiple pods and containers are contending for CPU bursting capacity. Which containers will get the extra CPU time, and how much of it will they get?

A pedantically correct engineering answer is: It depends, because we haven’t really talked about quality of service (QoS) classes yet and the cgroup hierarchy 🤓.

Cgroup hierarchy is another topic that I won’t do justice to in this high-level tour, but I’ll try and do a close enough pass-by of it to inform at least one interesting observation about Burstable pod and container behavior.

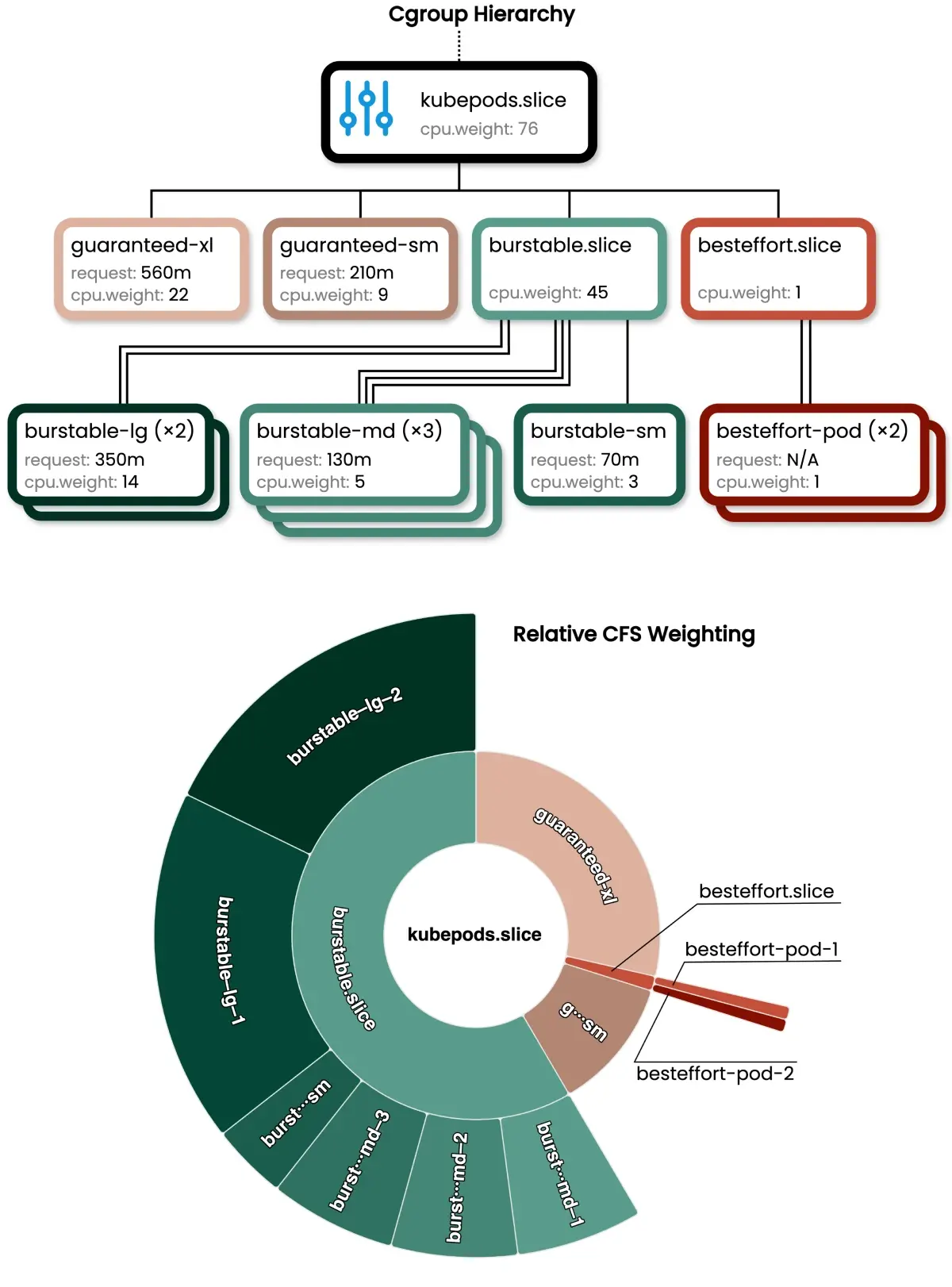

In the diagram below I’ve laid out an illustration of how Kubernetes sets up a cgroup hierarchy for QoS classes and pods, along with example cpu.weight values. Of specific note are the burstable.slice and besteffort.slice QoS groups, and their placement in the hierarchy.

The CliffsNotes for understanding this diagram are:

- Cgroups are configured in a hierarchy. They have layers, like onions.

- At each level, cgroups are allocated CPU time according to their

cpu.weight, proportional to same-level peers. - CPU time allocated to a cgroup at one level can be further subdivided among that cgroup’s children in the next level. The sub-allocation will be made the same way: Each child uses its

cpu.weightto compete (with its siblings) for a proportion of the CPU time allotted to the parent cgroup.

Therefore, in the context of how Kubernetes has set these groups up and according to the diagram above:

- Guaranteed QoS pods compete with: each other, a Burstable mega-parent and a BestEffort micro-parent.

- If even one Burstable QoS container wants CPU time, it will receive far more of the available “extra” cycles than Guaranteed or BestEffort QoS pods will, as a result of the proportional weight allotted to the Burstable mega-parent.

- Even if every BestEffort container on a node wants CPU time, their combined

cpu.weightcompeting against Guaranteed and Burstable QoS containers can never amount to more than the BestEffort micro-parent’s allotted weight of one.

There are a few nuances of behavior that emerge from this implementation, but the most interesting one is probably the following:

💡KEY OBSERVATION

Burstable CPU capacity is NOT distributed equally among containers. Rather, it is prioritized between containers according to relative CPU requests.

BestEffort QoS pods and containers can become CPU-starved very easily. All it takes is a single Burstable QoS container competing for spare CPU time on a node. The Burstable QoS container doesn’t even need to have directly requested any CPU resources itself, as long as its QoS class is Burstable.

Burstable QoS containers with no CPU requests might become CPU-starved under the same circumstances, though likely to a smaller degree. A Burstable container with cpu.weight of one will at least compete on even footing with other Burstable QoS containers.

For truly best-effort workloads with no minimum performance requirements or sensitivities, this bursting prioritization behavior might be highly desirable. However, when a workload has any minimum requirements at all, this inequitable allocation of CPU bursting capacity could be unexpected or problematic.

The risk of unintentional CPU starvation can be avoided one of two ways:

- The most reliable way to ensure a minimum CPU allocation is to have the workload request it. Set CPU requests for every container that needs them, and set them to the Right™ value. (What’s the Right™ value? Great question.)

- An alternative, and possibly more complicated mitigation strategy, might be to try and use CPU limits to tamp down CPU usage by the most likely Bad Actors™ or greedy CPU consumers.

The limits approach can feel tempting at first, but an industry consensus has been building around not using CPU limits at all for general-purpose workload templates, and relying on the request method instead. As we’ll see in the next section, CPU limits bring with them their own set of downsides and performance trip-ups.

CPU Limits: Put The Process in a Time-Out #

When you define Kubernetes CPU limits for your containers, the container runtime will translate that into cpu.max values on the container’s cgroup and the container’s processes will become subject to CFS’s bandwidth control mechanism.

The key concepts to understand about CFS bandwidth control are:

- Bandwidth control is based on periods (of time).

- CPU quota, if assigned, is set in terms of run-time (microseconds) granted each period.

- As soon as the CFS accounting system determines that a process has consumed all of its quota for a period, the process becomes throttled. While throttled, the process is effectively paused.

- At the beginning of each period, quota is refreshed and throttled processes become runnable again.

The cpu.max is configured by setting a MAX PERIOD string, where MAX is the number of microseconds the group can run for in each PERIOD (µs).

It can go deeper. This foundation is the bare minimum needed to understand CPU limits and throttling in Kubernetes. If you want to really dig in, there are many great articles out there that dissect additional CFS bandwidth controls, and specific edge cases related to how the runtime accounting system works.

In a nutshell-level of detail, here is the snarl that’s pushing the industry toward eschewing limits, and trying to get their guarantees from properly set CPU requests / cpu.weight instead.

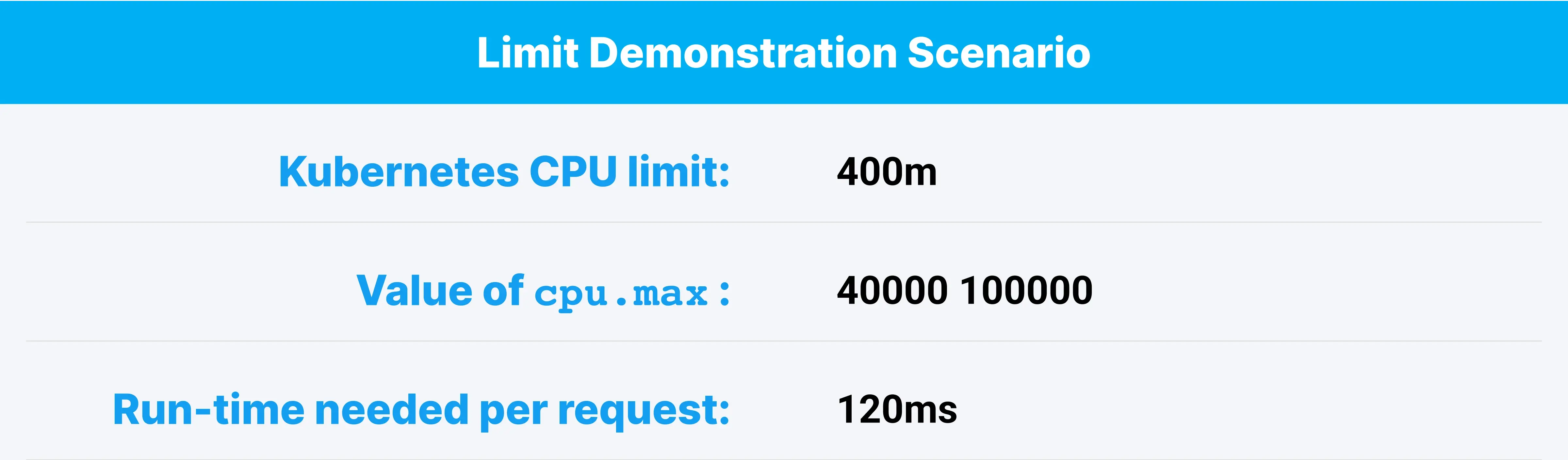

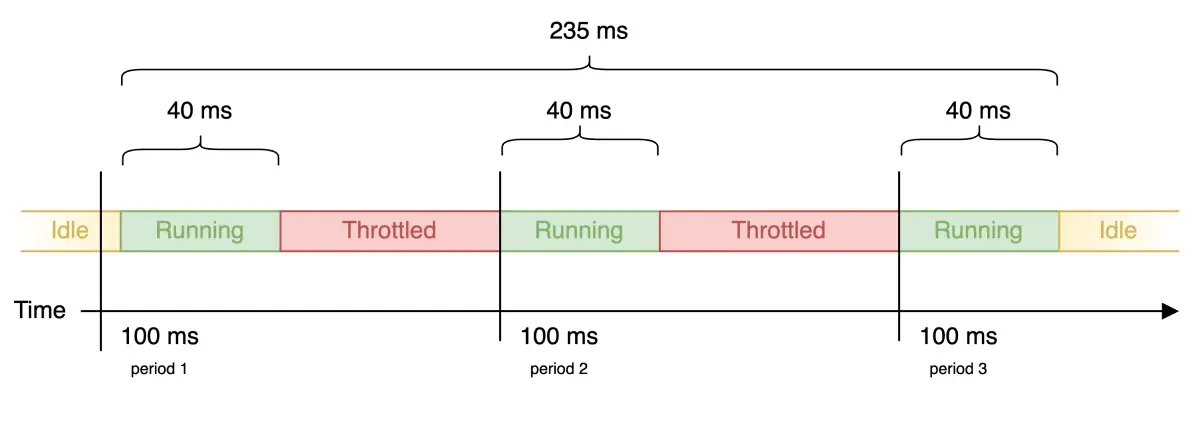

Suppose you have an app that needs 120ms of CPU time to process a request. For simplicity, let’s assume a quota period of 100ms (Kubernetes’ default), and a CPU limit of 400m. With our 100ms quota period, 400m = 4/10 = 2/5 = 0.4 of each period, or 40ms out of each 100ms period. Since cpu.max uses microseconds there’ll be a few more zeroes in the literal value set, so it’ll come out to 40000 100000 there, but we can continue to use 40ms and 100ms in the discussion.

The following diagram shows what might happen to latency for this app for one request, even if no other processes are running on the node.

While this is arguably exactly what a limit is intended to do, when looking at the app in isolation, there’s a potential lost opportunity here. If no other processes were contending for CPU time while this request was being processed, then throttling introduced an avoidable 115ms of latency. During that time, the CPU was not being used for anything else.

Limits always introduce a constraint on apps that can affect latency. Limits are constraint-oriented. So why would you typically want to introduce this kind of isolated constraint?

Answer: Typically, you wouldn’t.

People usually intuit that limits are related to fairness, and making sure every workload gets its allotted time. But as we’ve learned, that’s not actually true. Limits themselves aren’t the guarantors of runtime. Runtime allocation guarantees come from CPU requests, not limits. The only thing limits definitely do is prevent individual applications from making use of extra CPU time on the node, if any happens to be available.

💡KEY OBSERVATION

CFS throttling introduces avoidable latency in Kubernetes applications. Throttling can reduce node-level CPU efficiency, and doesn't provide any direct workload-level benefit.

CPU limits should not be applied to Kubernetes workloads as a general policy. Appropriate justification for setting limits is unlikely to relate to resource efficiency or “good neighbor” concerns, for most workload types.

CPU requests are the better guarantors of CPU time, and they’re also better at ensuring “good neighbor” behavior. When requests are set with the “right” values, limits are redundant.

The Journey Continues: Deep Dive into Memory #

With CPU and CFS cgroup settings out of the way, it’s time to move on to memory. How do memory requests and limits translate to Linux process settings? Will proportionality modeling apply to memory the same way it does to CPU? What happens, and why, when memory contention occurs on a node, and how do requests and limits factor into the result?

With Kubernetes’ cgroups fundamentals firmly under our belt, we reset, pivot and turn our attention to Linux memory resource implementation details next in Chapter 3.